In 2004, when color printers were still somewhat novel, PCWorld magazine published an article headlined: “Government Uses Color Laser Printer Technology to Track Documents.”

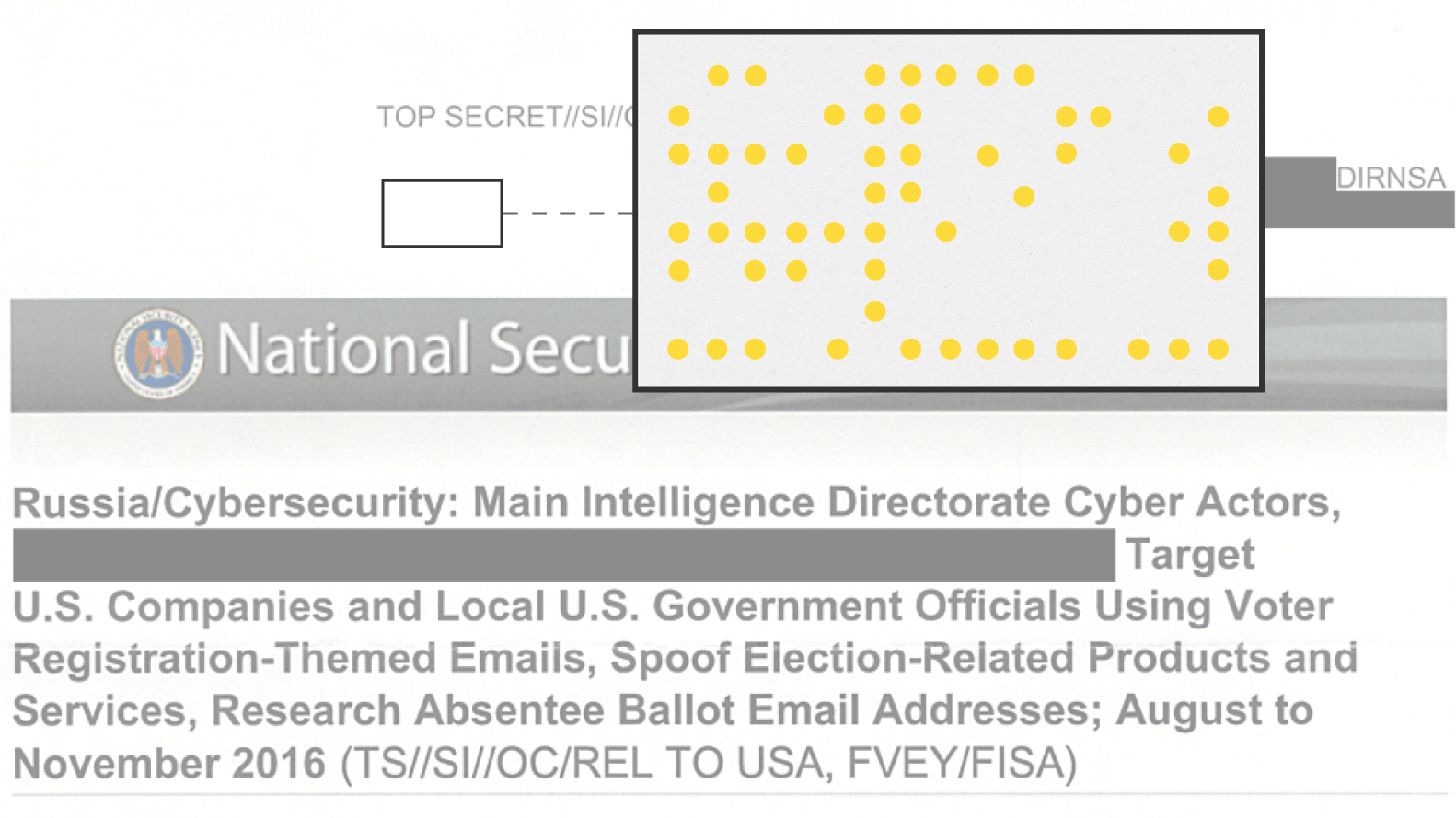

It was one of the first news reports on a quiet practice that had been going on for 20 years. It revealed that color printers embed in printed documents coded patterns that contain the printer’s serial number, and the date and time the documents were printed. The patterns are made up of dots, less than a millimeter in diameter and a shade of yellow that, when placed on a white background, cannot be detected by the naked eye.

In 2004, when color printers were still somewhat novel, PCWorld magazine published an article headlined: “Government Uses Color Laser Printer Technology to Track Documents.”

It was one of the first news reports on a quiet practice that had been going on for 20 years. It revealed that color printers embed in printed documents coded patterns that contain the printer’s serial number, and the date and time the documents were printed. The patterns are made up of dots, less than a millimeter in diameter and a shade of yellow that, when placed on a white background, cannot be detected by the naked eye.

The 2004 article in PCWorld was based on information provided by Peter Crean, who was a senior research fellow at Xerox at the time. In his first public interview about the practice since talking to the magazine 13 years ago, Crean told Quartz that Xerox hadn’t done much to share information about the dots’ existence.

“We didn’t advertise it much to the people that had [the printers],” said Crean, now retired. “We didn’t not tell them if they asked. The salespeople were told, ‘Don’t lead with it in any sales, but if they ask you about it, you can tell them we have the security feature in there.’”

When color printers were first introduced, he said, governments were worried the devices would be used for all sorts of forgery, particularly counterfeiting money. An early solution came from Japan, where the yellow-dot technology, known as printer steganography, was originally developed as a security measure.

Fuji, which has been in a joint-venture partnership with Xerox since 1962, was the first to implement the codes in printers. Fuji-Xerox manufactures most of Xerox’s printing and copying devices, and has done so for several decades. Amid rampant counterfeiting issues in Japan in the mid-1980s, Crean said, the company began programming color printers to embed the dots.

“They put it on early and we went along with it,” Crean said, “because the machines came with it.”

There are no laws or regulations in the US that force printer manufacturers to include the tracking codes. It became standard practice primarily because some countries would have refused to import the products without some assurance that if the printers were used to counterfeit money, they’d be able to track the owners down. If Xerox hadn’t implemented steganography in its early color printers, the US may have tried to block their import from Japan, Crean said.

In addition to the yellow-dot technology, Xerox implemented another feature around the same time that forced color copiers to shut down if they detected steganography in documents indicating they were currency. In 1994, the US Central Intelligence Agency approached Xerox about using the same technology to stop the unauthorized copying of classified documents, and Crean provided some ideas in a brainstorming session with two agents that year, he said. He wasn’t aware of whether the agency used any of his ideas, but the functionality to detect currency, he said, “was in most of the machines at least through the mid-2000s.”

When Crean talked to PCWorld in 2004, Xerox had been pushing a PR campaign focused on the technology and science behind some of its innovations, including steganography. The company had asked Crean to highlight the tech as a neat security feature the company’s printers included, and to talk about the science behind it. Crean had talked publicly about the codes a few times before, and nothing much had come of it. The company likely assumed the techie readers of PCWorld would get a kick out of the obscure feature.

“Our PR people set it up for me,” said Crean. “When I gave the interview at my desk, our PR person was sitting right across the desk from me, nodding at everything I said.”

The article created an uproar among privacy advocates, who said the practice was a violation of Americans’ constitutional rights. Although the article quoted a Secret Service counterfeiting specialist, who said “the only time any information is gained from these documents is purely in [the case of] a criminal act,” privacy advocates pointed out there were no laws to hold the government to that.

“The possible misuses of this marking technology are frightening,” wrote the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) in a blog post responding to the article. “Individuals using printers to create political pamphlets, organize legal protest activities, or even discuss private medical conditions or sensitive personal topics can be identified by the government with no legal process, no judicial oversight, and no notice to the person spied upon.”

Salespeople at Xerox were told at this point to refer all questions about the dots to Xerox headquarters, Crean said.

A security researcher at the EFF, Seth Schoen, began looking into the dots shortly after the article was published, hoping to figure out how to read the encoded patterns. The organization asked the public to submit samples of their own printed documents, Schoen said, which helped them to compare differences between patterns on many printer models.

“We also went to a number of Kinko’s locations and printed our own samples, which is a great way to get DocuColor samples,” Schoen said, referring to Xerox model they were researching. “We looked at them with scanners and microscopes (and blue-light flashlights).”

Eventually, a volunteer working with the EFF noticed that the dots represented a binary code, Schoen said. It allowed them to crack the logic behind them, and to read the information embedded in any document that used yellow-dot steganography. The organization published the results of its work, along with an interactive tool to decode the dots.

The researchers also published a list of all the models they found that embed the same pattern of dots, but Schoen pointed out in a phone interview that we should assume every color printer embeds tracking information in one way or another. He referred to information the EFF obtained in 2005 through a Freedom of Information Act request to the US government.

“Some of the documents that we previously received through FOIA suggested that all major manufacturers of color laser printers entered a secret agreement with governments to ensure that the output of those printers is forensically traceable,” the EFF said on its website.

Indeed, Crean said that after Fuji-Xerox began embedding tracking codes, the practice became ubiquitous.

“Other companies came up with other variants of that scheme that were more complicated, harder to decode. Canon kind of twist theirs around in a spiral,” Crean said, “but everybody was basically putting a small digital set of bits smack dab all over the print.”

Xerox, HP, Canon, and the NSA did not immediately respond to our requests for comment.

Although the code behind the yellow-dot patterns was cracked, there is likely other steganography still in use that has yet to be discovered. In addition to the various implementations Crean mentioned, Schoen said there is at least one newer version that is even more difficult to find in a document.

“What we’ve learned is that there is a second generation of the technology that some of the manufacturers have switched over to,” Schoen said. “We’ve never cracked that or even had a way to detect it.”

[“Source-ndtv”]